We collect basic website visitor information on this website and store it in cookies. We also utilize Google Analytics to track page view information to assist us in improving our website.

Written by: Bianca Marcellino

The Tundra biome is characterized by extreme cold weather, low biotic diversity and precipitation levels, short growing seasons, low-growing vegetation of simple structure, and nutrients available mostly in the form of dead organic matter. Only a small portion of the permafrost thaws each growing season, called the active layer, which limits the vegetation to low shrubs, sedges, flowering plants, and mosses, all with shallow roots and short reproductive cycles.

In recent decades, the Tundra has rapidly warmed causing a variety of environmental effects including: melting sea ice resulting in increased water levels, shifting vegetation ranges, and release of CO2 stored in the permafrost. Presently, northern Tundra soils hold ~30% of the total soil organic carbon, which with the continued increase in temperature expected to occur over the next decades, threatening the release of this carbon sink; has alarmed the scientific community and gained the name the “Carbon Bomb”.

The warming temperatures may promote the expansion of the Canadian population into previously sparse areas such as the Tundra, fostered by the increased ability of the Tundra to support a greater abundance of vegetation (Deslippe 2011). This activity serves to counteract the lurking prospect of the carbon bomb ‘explosion’; however, the warming temperatures are also expected to drive native Arctic species further North if they are unable to adapt to the warming climate of their original regions. It is unclear whether the release of atmospheric carbon through the thawing of the permafrost will result in the Tundra becoming a carbon source via heightened microbial activity, or remain a carbon sink through increased vegetation growth.

The question arises - is it possible to plant native Arctic plants, which are well adapted to the current Tundra climate, as a mitigation strategy to help combat the “Carbon Bomb”? This could act to support Artic herbivores and their subsequent food webs, and potentially help to limit their displacement to more Northern areas, but may be impractical given the scale of the Canadian arctic and the limitations in our knowledge of how arctic ecosystems are being impacted by climate change.

The question arises - is it possible to plant native Arctic plants, which are well adapted to the current Tundra climate, as a mitigation strategy to help combat the “Carbon Bomb”? This could act to support Artic herbivores and their subsequent food webs, and potentially help to limit their displacement to more Northern areas, but may be impractical given the scale of the Canadian arctic and the limitations in our knowledge of how arctic ecosystems are being impacted by climate change.

This uncertainty clearly identifies the need for further study of Canada’s arctic in order to find the best tools to combat the carbon bomb.

Additonal Reading

National Geographic - Tundra Threats Explained

The Narwhal - Arctic tundra is 80 per cent permafrost. What happens when it thaws?

Sciencing - Plant Adaptations in the Tundra

References

Deslippe, J. R., M. Hartmann, W. W. Mohn and S. W. Simard. 2011. Long-term experimental manipulation of climate alters the ectomycorrhizal community of Betula nana in Arctic tundra. Global Change Biology. 17:1625-1636.

Gilg, O., K. M. Kovacs, J. Aars, J. Fort, G. Gauthier, D. Grémillet, R. A. Ims, H. Meltofte, J. Moreau, E. Post, N. M. Schmidt, G. Yannic and L. Bollache. 2012. Climate change and the ecology and evolution of Arctic vertebrates. The Year in Ecology and Conservation Biology 1249:166-190.

Steiglitz, M., A. Giblin, J. Hobbie, M. Williams and G. Kling. 2000. Stimulating the effects of climate change variability on carbon dynamics in Arctic tundra. Global Biochemical Cycles 14:1123-1136.

Treat, C. C. and S. Frolking. 2013. A permafrost carbon bomb? Nature Climate Change 3:865-867.

UC Berkeley Biomes Group, S. Pullen and K. Ballard. 2004. The Tundra Biome. Berkeley University of California. Berkeley, CA, USA.

Written by: Cole White

This year's UN World Wildlife Day celebrates forest-based livelihoods worldwide with the theme 'Forests and Livelihoods: Sustaining People and Planet'.

I grew up a family who hunted, fished, and worked in the woods. Later, like many young Canadians, I laboured as a piecework tree planter in the Boreal Forest. But even people I know who have lived their lives in Canada's most urban neighbourhoods feel a connection to woodlands—for example, my Torontonian friends who feel a sense of integration when they visit High Park, the ravines of the Don River, or the Rouge Valley.

Forests are a cornerstone of Canadian life. Everywhere, plants, microbes, birds, fish and a myriad of other creatures—including us—exist as part of a rich biological schema including forests. In Canada, forests sustain our culture, economy, spirituality, and livelihoods in ways that make this land and its people what they are.

Thirty-nine percent of Canada's land is forest, and this represents 9% of the world's total forests. The future is unwritten, but these numbers tell us that state of Canadian forests is a major variable in how climate change will play out worldwide.

Of course, it's a given that the changes we're already seeing—including severe wildfires, loss of ecological diversity, and the proliferation of invasive species that threaten tree populations—are expected to become more extreme in the coming years.

Adding to this, economic changes due to the pandemic, evolving consumer demands (for example, the decline of print newspapers and magazines), and international competition show that the preexisting commercial relationship between Canadian forests and people won't be the way of the future.

Increasingly, many Canadians are recognizing what forests give them, and asking what they can do in return. To me, this year's World Wildlife Day theme (and this inspired illustration for the event by Gabe Wong) expresses a hope that our global communities are affirming their relationships with forests and finding constructive ways forward that honour our interdepedence.

What's happening right now in Canada to support this? Our country's issues are diverse and so multifaceted, but these are a few trends I've noticed recently:

Indigenous forest management systems offer expertise informed by thousands of years' experience working with this land. The most recent Canadian census reported that 70% of Indigenous people in Canada live in or near forests. (I've also seen similar statistics for other parts of the world, and globally.) Increasingly, Indigenous people are reclaiming portions of their original territories and asserting their right to participate in self-governance, including forest management.

Indigenous involvement in sustainable natural resource management is helping to bring socio-economic benefits to communities and maintain cultural, recreational, and spiritual connections to the land. As reported beautifully in the National Observer, residents of B.C.'s Tŝilhqot'in Nation are using clean energy to develop a new land, water, and wildlife management area, supporting self-determination within their communities.

Coastal Guardian Watchmen also provide a model for what responsible land stewardship can look like in Haida Gwaii.

It's exciting to see collaborative efforts undertaken to synergize traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) and settlers' science-based understanding of nature as complementary information systems.

In a recent lecture, Indigenous scholar and assistant professor Myrle Ballard at the University of Manitoba described how Indigenous expertise can inform scientific work.

The viewpoint has also been expressed poetically in the best-selling Braiding Sweetgrass, by botanist Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer, who espouses radical gratitude to nature by asking that humans consider the question, 'What can I give in return for the gifts of the earth?'

Landscape architects and horticulturalists are inventing and adapting design models that enhance vitality for people and forests.

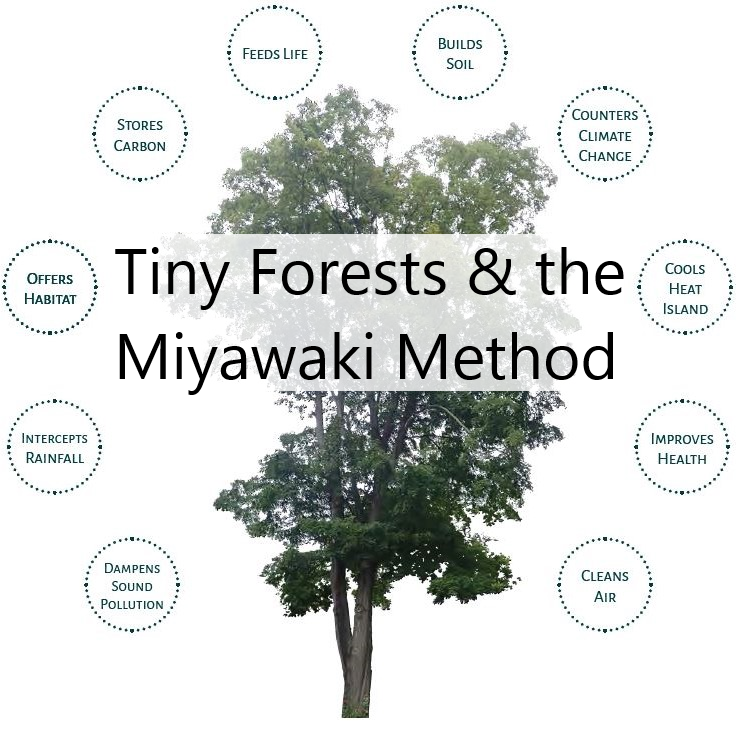

Planting individual trees is great, but what if you could fast-track the growth of a mini forest community in your neighbourhood? Network of Nature is piloting a new project on using the Miyawaki Forest technique to do just that in Canada.

Emerging technologies have their place in this work:

Remote sensing and artifical intelligence can give us new eyes in the sky to monitor our expansive Boreal Forest for extreme wildfires.

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) analysis and interpretitive web cartography are being used to understand and educate Canadians about the value of our northern peatlands.

Ex-situ conservation methods carried out in sterile labs are providing hope for at-risk species, with researchers developing tissue culture and seed banking methodologies to preserve genetically unique local flora.

I think that Gen Z will grow up more attuned to ecological issues than any previous generation. One educational resource I noticed recently is this kid-friendly website, which includes a colouring book, advocating for the conservation of Wisqoq (Black Ash) populations in our eastern forests.

Black Ash(Fraxinus nigra) Black Ash is native to Eastern Canada and is used in traditional basket weaving. Populations are currently under threat due to the proliferation of Emerald Ash Borer.

|

|

This blog post is a snapshot of my personal reflections, and I'm sure I don't have all the pieces of the puzzle. Maybe you have something to add about how Canadians and forests can work together, or where this is all going. Do you know of something I should have mentioned here? Let us know!

For more information about World Wildlife Day events, which include a film festival, check out the offical website.

Join our email list to receive occasional updates about Network of Nature and ensure you get the news that matters most, right in your inbox.