We collect basic website visitor information on this website and store it in cookies. We also utilize Google Analytics to track page view information to assist us in improving our website.

Written by: Ryan Smith

Forests cover about 31% of the world's land area (FRA 2020), playing a critical role in maintaining ecological balance, supporting biodiversity, and providing livelihoods for millions of people. Yet these vital ecosystems are under unprecedented threat. In the coming decades, the diminishing availability of productive land, competition from other land uses, and climate change will increasingly place global forests under threat (Kissinger, Herold, & De Sy, 2012).

Artificial Intelligence (AI) may serve as a powerful tool to reverse the adverse effects of human activity on forested areas. This technology's capacity to analyze vast datasets to make insightful predictions can significantly enhance our approach to forest management. In doing so, AI propels us towards a sustainable coexistence with these vital ecosystems, ensuring their preservation for future generations.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is a branch of computer science dedicated to creating machines capable of performing tasks that typically require human intelligence. At its core, AI involves the development of algorithms and computational processes that enable computers to learn from data, make decisions, and solve problems. This technology spans several fields, including machine learning, natural language processing, robotics, and computer vision, each contributing to the vast capabilities of AI systems. In forest conservation solutions, machine learning, a subset of AI, has become instrumental in analyzing complex environmental data, enabling predictive modeling for monitoring deforestation and land use changes, predicting and managing wildfires, and species distribution mapping (Perry et al., 2022).

The world has a total forest area of 4.06 billion hectares (ha) of forest as of 2020 (FRA 2020). Regulating activities that result in canopy loss such as logging, agricultural expansion and mining is essential for protecting forest ecosystems. Ensuring regulatory compliance is crucial but is often challenged by the high costs associated with manual monitoring. Employing AI solutions can help to reduce labour cost on compliance monitoring and improve accuracy. By processing vast amounts of satellite data, AI can pinpoint areas of deforestation, track the expansion of agricultural lands into forested territories, and detect signs of illegal logging activities. This real-time surveillance allows for immediate action, facilitating interventions before irreversible damage occurs.

The advent of AI has opened new horizons in predicting and managing wildfires, a threat that is becoming increasingly frequent and severe due to climate change (Flannigan et al., 2009). By harnessing the power of AI algorithms, we can now analyze vast datasets encompassing weather patterns, historical fire occurrences, and other environmental factors, providing predictive insight necessary to foresee wildfire outbreaks. This predictive capability is not just about foreseeing the occurrence of fires but also about understanding their potential severity, spread, and impact on ecosystems and human settlements.

It is widely accepted that the emergence of the human industrial era is responsible for the ongoing 6th global mass extinction event. Vertebrate species loss over the last century is up to 100 times higher than the background rate, indicating that a sixth mass extinction is already underway (Ceballos et al., 2015). Implementing conservation strategies around our forests is vital for the protection of our biodiversity. The identification of key habitat features to better understand species presence, abundance and distribution is essential to effectively implement targeted conservation strategies. Gathering this data at a landscape level is very costly.

AI plays a crucial role in mitigating these costs and enhancing the effectiveness of conservation strategies. AI can analyze vast amounts of data from satellite imagery, drones, and sensor networks to identify key habitat features with unprecedented speed and accuracy. This capability enables conservationists to monitor wildlife populations, track changes in habitat quality, and predict potential threats to biodiversity with a level of detail that was previously unattainable.

The Muskoka Integrated Watershed Management project located in Central Ontario was completed by Dougan & Associates in 2023. The project leveraged advanced AI technologies, particularly in GIS modeling and machine learning, to enhance watershed management and species conservation. By employing deep learning and GIS modeling, powered by high-resolution LiDAR data and multispectral imagery, the project achieved detailed classification of terrestrial, wetland, and aquatic systems. This precise land cover mapping facilitated the identification of ecologically significant areas, including habitats for rare and endangered species. Machine learning models were employed to predict potential locations for select species based on their habitat preferences and known occurrences. This methodology not only refined the understanding of land cover types within the watershed but also enhanced habitat suitability models for wildlife conservation. The combined use of cutting-edge technologies ensured an accurate and comprehensive assessment of natural capital, crucial for integrated watershed management and ecological preservation.

The potential for AI to have a positive impact on forest conservation is profound, yet its application in this field is still in the early stages of adoption. To effectively utilize AI for forest conservation, a collaborative and holistic strategy is vital. Collaborative investment is needed from the private and public sector tailored for environmental preservation, involving interdisciplinary efforts that blend computer and ecological sciences. Policy frameworks must evolve to support AI's role in forest management, encouraging the open sharing of environmental data and enforcing AI-driven compliance monitoring.

References

Ceballos, G., Ehrlich, P. R., Barnosky, A. D., García, A., Pringle, R. M., & Palmer, T. M. (2015). Accelerated modern human-induced species losses: Entering the sixth mass extinction. Science Advances, 1(5), e1400253. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1400253

Flannigan, M., Krawchuk, M., Groot, W., Wotton, B., & Gowman, L. (2009). Implications of changing climate for global wildland fire. International Journal of Wildland Fire, 18, 483-507. https://doi.org/10.1071/WF08187.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2020). Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020: Key findings. FAO. http://www.fao.org/forest-resources-assessment/2020/en/

G. L. W. Perry, R. Seidl, A. M. Bellvé, W. Rammer, An outlook for deep learning in ecosystem science. Ecosystems 25, 1700–1718 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-022-00789-y.

Kissinger, G., M. Herold, V. De Sy. Drivers of Deforestation and Forest Degradation: A Synthesis Report for REDD+ Policymakers. Lexeme Consulting, Vancouver Canada, August 2012.

Written by: Cole White

There are many ways of understanding plants. Scientific study, home gardening, ecological restoration work, and traditional knowledge modalities all offer people significant ways to meaningfully connect with plants and gain an appreciation for the services and beauty they offer.

My interest started with growing up in a rural area and being intrigued by the wild edible plants, such as Lamb's Quarters and Mint, that could be found in my backyard. Later I worked at a botanical garden, which got me interested in more big-picture topics like forest succession and pollination. Now, as a GIS technician at Dougan and Associates and part of the Network of Nature team, I often engage with plant knowledge using data, and databases.

The species pages you can explore on the Network of Nature website are powered by an underlying database– that is, an organized collection stored and accessed on a computer. This database contains names, photographs, and various traits (such as native and introduced geographic ranges, bloom colour, and compaction tolerance) for about 5,000 plant species that occur in Canada, all stored in a way that is structured and easily retrieved, modified, or analyzed.

While there may be nuances of biology a typical database system cannot capture, and complex questions these technologies cannot answer in full, the beauty of storing information this way is that it allows us to analyze the collected data in ways that can give us useful (or at least interesting) insights, or raise new questions to inspire further investigation.

One question we recently considered is what a phylogenetic tree created from the Network of Nature database would look like and what further research and exploration this could inspire.

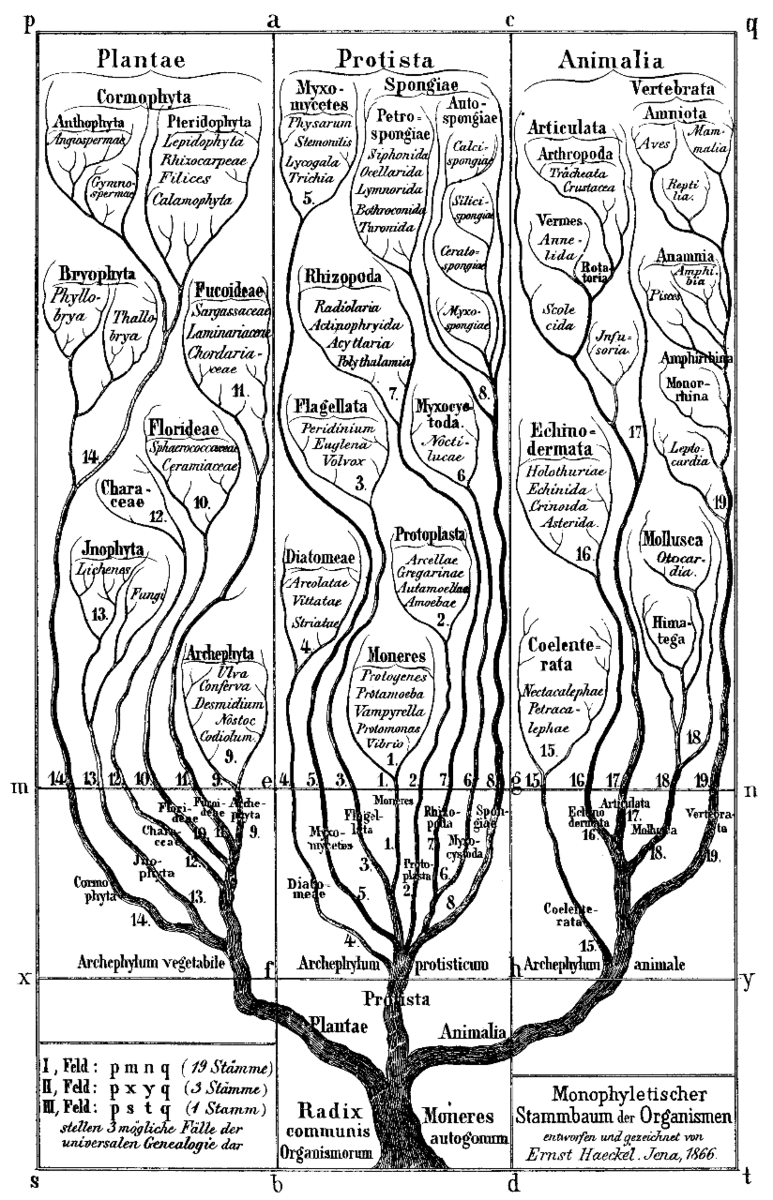

A phylogenetic tree (or 'tree of life') is a branching diagram, visually tracing the evolutionary lineage of a set of organisms back to a common ancestor. All of life on Earth could be traced back to a single ancestor this way. Phylogenetic trees created from more specific datasets are increasingly being used in ecological and biogeographic studies that allow us to learn more about biology and evolution.

A 19th-century phylogenetic tree.

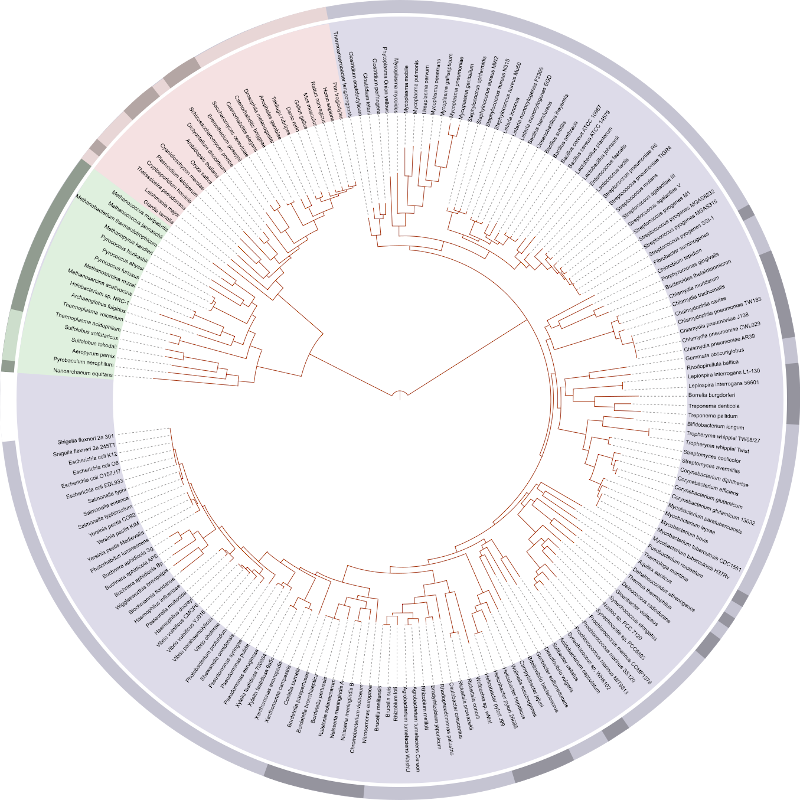

Phylogenetic trees used to be hand-drafted by scientists, but can now be created quickly and easily using open source tools developed by unselfish computer programmers. I used the R programming language and an R package called V.Phylomaker to generate a phylogeny based on the Network of Nature database, and a Neo4j graph to store and visualize the results.

A modern tree of life based on genome sequencing.

R is a programming language widely used by statisticians and data analysts. It incorporates machine learning, linear regression, statistical inference, and other techniques to perform data science work that has applications in many different fields.

The things R can do are extended by add-ons called packages. One of these packages is V.Phylomaker, which uses a 'mega-tree' containing data related to all extant flowering plant families to build phylogenetic trees from a simple spreadsheet of plant species information.

A list of species exported from Network of Nature.

Neo4j is a type of database that focuses on relationships between entities, rather than just storing rows of data. We thought this would work as an interesting tool to model the relationships between plant species.

To try this out with Network of Nature, I installed the package and used an export of the Network of Nature database as an input for a small R script using V.Phylomaker. The output of this was a phylogenetic tree in Newick format, a mathematical way of representing this kind of data.

Working with plant data in RStudio.

Next, I used a Python script and the Biopython package to read this Newick data and use it to populate a Neo4j graph.

The result was a dataset of interconnected plant species that could easily be visualized, queried, and explored.

A Network of Nature phylogenetic tree visualized using a graph.

We’re excited to continue exploring the benefits of incorporating a phylogenetic approach into the Network of Nature database. We anticipate that capturing evolutionary relationships among plants will help to deepen our collective understanding of the diversity of plant species found across Canada, and advance the tools and approaches that are used in conservation planning, ecological restoration, gardening, and a wide range of other biodiversity initiatives.

Feel free to reach out to our team if you’re interested to learn more about what we’re doing at Network of Nature.

Written by: Cole White

This year's UN World Wildlife Day celebrates forest-based livelihoods worldwide with the theme 'Forests and Livelihoods: Sustaining People and Planet'.

I grew up a family who hunted, fished, and worked in the woods. Later, like many young Canadians, I laboured as a piecework tree planter in the Boreal Forest. But even people I know who have lived their lives in Canada's most urban neighbourhoods feel a connection to woodlands—for example, my Torontonian friends who feel a sense of integration when they visit High Park, the ravines of the Don River, or the Rouge Valley.

Forests are a cornerstone of Canadian life. Everywhere, plants, microbes, birds, fish and a myriad of other creatures—including us—exist as part of a rich biological schema including forests. In Canada, forests sustain our culture, economy, spirituality, and livelihoods in ways that make this land and its people what they are.

Thirty-nine percent of Canada's land is forest, and this represents 9% of the world's total forests. The future is unwritten, but these numbers tell us that state of Canadian forests is a major variable in how climate change will play out worldwide.

Of course, it's a given that the changes we're already seeing—including severe wildfires, loss of ecological diversity, and the proliferation of invasive species that threaten tree populations—are expected to become more extreme in the coming years.

Adding to this, economic changes due to the pandemic, evolving consumer demands (for example, the decline of print newspapers and magazines), and international competition show that the preexisting commercial relationship between Canadian forests and people won't be the way of the future.

Increasingly, many Canadians are recognizing what forests give them, and asking what they can do in return. To me, this year's World Wildlife Day theme (and this inspired illustration for the event by Gabe Wong) expresses a hope that our global communities are affirming their relationships with forests and finding constructive ways forward that honour our interdepedence.

What's happening right now in Canada to support this? Our country's issues are diverse and so multifaceted, but these are a few trends I've noticed recently:

Indigenous forest management systems offer expertise informed by thousands of years' experience working with this land. The most recent Canadian census reported that 70% of Indigenous people in Canada live in or near forests. (I've also seen similar statistics for other parts of the world, and globally.) Increasingly, Indigenous people are reclaiming portions of their original territories and asserting their right to participate in self-governance, including forest management.

Indigenous involvement in sustainable natural resource management is helping to bring socio-economic benefits to communities and maintain cultural, recreational, and spiritual connections to the land. As reported beautifully in the National Observer, residents of B.C.'s Tŝilhqot'in Nation are using clean energy to develop a new land, water, and wildlife management area, supporting self-determination within their communities.

Coastal Guardian Watchmen also provide a model for what responsible land stewardship can look like in Haida Gwaii.

It's exciting to see collaborative efforts undertaken to synergize traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) and settlers' science-based understanding of nature as complementary information systems.

In a recent lecture, Indigenous scholar and assistant professor Myrle Ballard at the University of Manitoba described how Indigenous expertise can inform scientific work.

The viewpoint has also been expressed poetically in the best-selling Braiding Sweetgrass, by botanist Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer, who espouses radical gratitude to nature by asking that humans consider the question, 'What can I give in return for the gifts of the earth?'

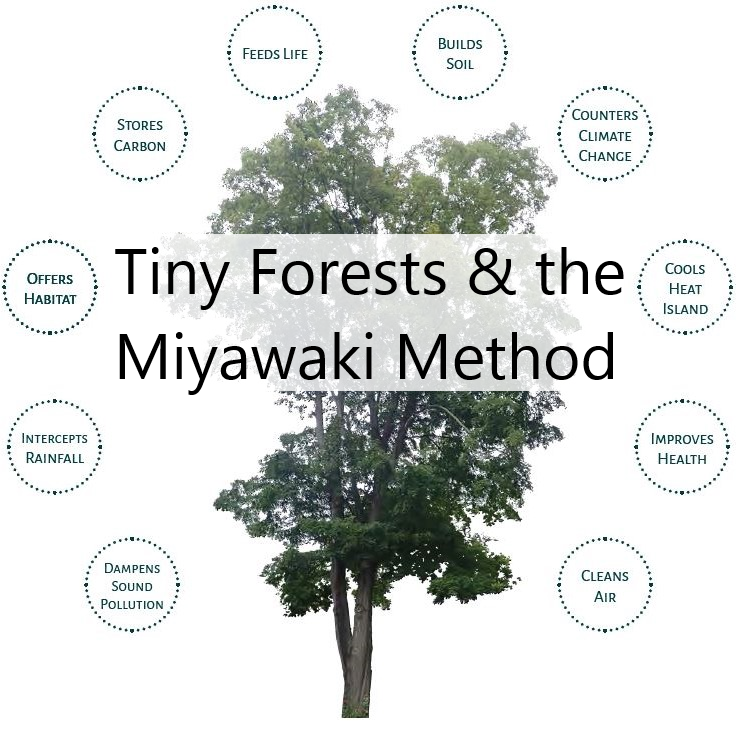

Landscape architects and horticulturalists are inventing and adapting design models that enhance vitality for people and forests.

Planting individual trees is great, but what if you could fast-track the growth of a mini forest community in your neighbourhood? Network of Nature is piloting a new project on using the Miyawaki Forest technique to do just that in Canada.

Emerging technologies have their place in this work:

Remote sensing and artifical intelligence can give us new eyes in the sky to monitor our expansive Boreal Forest for extreme wildfires.

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) analysis and interpretitive web cartography are being used to understand and educate Canadians about the value of our northern peatlands.

Ex-situ conservation methods carried out in sterile labs are providing hope for at-risk species, with researchers developing tissue culture and seed banking methodologies to preserve genetically unique local flora.

I think that Gen Z will grow up more attuned to ecological issues than any previous generation. One educational resource I noticed recently is this kid-friendly website, which includes a colouring book, advocating for the conservation of Wisqoq (Black Ash) populations in our eastern forests.

Black Ash(Fraxinus nigra) Black Ash is native to Eastern Canada and is used in traditional basket weaving. Populations are currently under threat due to the proliferation of Emerald Ash Borer.

|

|

This blog post is a snapshot of my personal reflections, and I'm sure I don't have all the pieces of the puzzle. Maybe you have something to add about how Canadians and forests can work together, or where this is all going. Do you know of something I should have mentioned here? Let us know!

For more information about World Wildlife Day events, which include a film festival, check out the offical website.

Join our email list to receive occasional updates about Network of Nature and ensure you get the news that matters most, right in your inbox.