We collect basic website visitor information on this website and store it in cookies. We also utilize Google Analytics to track page view information to assist us in improving our website.

Written by: Summer Graham

If you find yourself constantly heading to Google to search for answers about native plants, then today is your lucky day! We are tackling some of the most searched questions about native plant species - what they are, what they do, why they are good, and where to find them!

First off, what does it even mean to be native? The question of whether a plant is native or introduced may differ depending on the source you are using and which geographical area you are referring to. For example, a plant can be native to Canada, but not native to certain provinces (e.g. Manitoba Maple). You may have noticed that some sources even differ in their display of native species ranges.

The term native is defined as “of indigenous origin or growth”. Native species are therefore defined as those which originate from a given area prior to human intervention. These species have evolved over thousands of generations as part of a cohesive ecosystem alongside other native wildlife and have adapted to the environmental conditions present in a region.

Most species deemed “non-native” or “invasive” to an area are often brought through human intervention, many of which can be timed to European settlement of North America. Think Common Buckthorn brought to North America to be a hedge tree, and Garlic Mustard introduced as a food source for European settlers. Not all non-native species were brought over intentionally however, Zebra Mussels hitched a ride in ballast water, and Emerald Ash Borer is thought to have come to North America on wooden shipping pallets.

Overall, it can be difficult to trace a species origin and in a changing climate, species ranges are constantly moving. This leads to much debate over what is truly a “native” species.

Native plants provide a wide variety of benefits, including:

Like all plants, native plants require specific conditions to grow and thrive. Some species will do better in specific conditions (specialists) while others will be able to survive a variety conditions (generalists).

Levels of sun, and water, temperature requirements, soil preferences, and nutrients needed can vary greatly between species, and even within species growing in different regions. It is important to assess your site or garden prior to selecting species, so you can closely match the species you choose to the conditions you have! This will make it easier for your plants to establish without as much work from you.

Planting native trees at the Toronto Zoo Mini Forest - Madigan Cotterill/CanGeo

Native plants help the environment in a variety of ways, with one key impact being the restoration of degraded areas into natural ones. This helps to support local wildlife by providing food and habitat. Growing native plants in the proper conditions can also reduce the need for pesticides and fertilizers, which can cause harm to waterways if not used properly and allowed to run into streams or rivers.

Native plants are often promoted as being “better” for pollinators, but what exactly does this mean? Unlike introduced, non-native species, native plants have evolved alongside native wildlife for many years. This means that the wildlife have adapted to maximizing the benefit they gain from native plants, and native plants have evolved strategies to be pollinated or dispersed by native wildlife. In some cases, it has gone as far as a wildlife species needing a single type of plant for an essential part of its lifecycle (like how Monarch butterflies cannot reproduce without Milkweed). Native plants also provide the right nutrients for native species, with some studies finding that native pollinators get more energy from native pollen and nectar, reducing the amount of energy needed to collect food.

Native plants will follow the proper flowering cycle for their local climate. Some nonnative species will not bloom for as long, or at the right time, to support peak pollinator populations. Ideally, your pollinator garden will include native plants that bloom in early spring, species that bloom in summer, and late blooming species for fall.

Plants that are native “for your area” will obviously depend on where you are! There are many resources online and field guides that might be able to help, or you can visit our plant database and filter for your location to find species with the same native distribution! It is currently only possible to filter for species by province or territory, but keep in mind that a species suitable for the Carolinian range in Ontario won’t be suitable for the far north of the province, and vice versa! Look to local forests and natural plant communities in your area for an idea of the types of species that grow well wherever you are.

When selecting species to plant in your yard, remember that conditions matter! Just like any species, native plants have specific soil, sun, and moisture considerations. Carefully considering your site and choosing appropriate species will give you the best success.

There are many options for buying or sourcing native species for your garden! If you know someone who grows native plants in their yard, see if you can collect seed or cuttings from their plants to start your own garden. Some species may tolerate being divided and transplanted as well. You can also join local native plant gardening groups on social media for some great tips on growing native species and where to get them locally.

Many options also exist for purchasing native plants or seeds for your yard. Sourcing from local areas is the best option, as these species will have genetics suitable for the conditions in your area. For example, even though you can buy seeds for species native to your area online from California, they likely don’t have the same genetics as a species found closer to where you are in Ontario. Check local plant groups, arboretums and conservation authorities for native plant sales, and inquire at your local garden centre for native species. Many independent, native plant nurseries are also open to the public - to find where to buy native species near you, visit our “Find a native plant nursery” map here .

Written by: Rachel Pigden

In Ontario and beyond, the beloved monarch butterfly is known as a flagship species for pollinator conservation. Perhaps one of the biggest successes of the monarch conservation movement is its emphasis on the importance of native plants in protecting pollinators (and other wildlife). Milkweed (Asclepias sp.), once villainized as a noxious weed, is now recognized for its critical role as the sole food source for monarch larvae. But monarchs and milkweed are only part of the story—Ontario is home to several other butterflies-at-risk that rely on specific native plants to survive. Follow along as we profile some of these special butterfly-plant pairings.

Walk through a temperate forest in the early spring and you will be greeted by nature’s early risers: the spring ephemerals. These perennial plants are specialists that emerge and grow quickly early in the year, then die back and remain underground as warm weather approaches. While the spring ephemerals are known as harbingers of hope for those anxious for gardening season to begin, they also fill an important ecological niche by providing early food and habitat for wildlife.

One group of spring ephemerals, the Toothworts, is particularly important for  the West Virginia White, a small-to-medium white butterfly classified as species of special concern in Ontario. Toothworts are small perennials in the mustard (Brassicaceae) family; the favorite species of West Virginia Whites in Ontario is Two-leaved Toothwort (Cardamine diphylla). The West Virginia White is adapted to the fleeting nature of Toothwort: these butterflies hatch only one brood per year, from solitary eggs laid on the plants in early spring. Larvae feed for 10-20 days after hatching, then pupate and hibernate until the following spring, when adults once again emerge alongside their host plant and the cycle repeats.

the West Virginia White, a small-to-medium white butterfly classified as species of special concern in Ontario. Toothworts are small perennials in the mustard (Brassicaceae) family; the favorite species of West Virginia Whites in Ontario is Two-leaved Toothwort (Cardamine diphylla). The West Virginia White is adapted to the fleeting nature of Toothwort: these butterflies hatch only one brood per year, from solitary eggs laid on the plants in early spring. Larvae feed for 10-20 days after hatching, then pupate and hibernate until the following spring, when adults once again emerge alongside their host plant and the cycle repeats.

West Virginia Whites are found throughout the Great Lakes states and southern Ontario (some reports suggest they may be found in Quebec as well). Across their range, they face the same habitat loss and fragmentation, pressure common to many species adapted to interior forest habitats. These butterflies are strict forest specialists: they require continuous tree cover and are unable to adapt to common forest interruptions such as hydro corridors. Another significant threat to the species is invasive Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata)—and the problem is two-fold. Garlic Mustard not only outcompetes Toothwort in forest floors but is also toxic to West Virginia White larvae that hatch on the plants because adults are attracted to them.

fragmentation, pressure common to many species adapted to interior forest habitats. These butterflies are strict forest specialists: they require continuous tree cover and are unable to adapt to common forest interruptions such as hydro corridors. Another significant threat to the species is invasive Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata)—and the problem is two-fold. Garlic Mustard not only outcompetes Toothwort in forest floors but is also toxic to West Virginia White larvae that hatch on the plants because adults are attracted to them.

Written by: Rachel Pigden

In Ontario and beyond, the beloved monarch butterfly is known as a flagship species for pollinator conservation. Perhaps one of the biggest successes of the monarch conservation movement is its emphasis on the importance of native plants in protecting pollinators (and other wildlife). Milkweed (Asclepias sp.), once villainized as a noxious weed, is now recognized for its critical role as the sole food source for monarch larvae. But monarchs and milkweed are only part of the story—Ontario is home to several other butterflies-at-risk that rely on specific native plants to survive. Follow along as we profile some of these special butterfly-plant pairings.

New Jersey Tea (Ceanothus americanus) and the closely related but less common Prairie Redroot (C. herbaceus) are specialist shrubs adapted to some of Ontario’s most at-risk habitats: prairies, alvars, open woodlands and savannas. Belonging to the Rhamnaceae (Buckthorn) family, these two species and their associated habitats evolved alongside fire: periodic low-grade burning prevents later successional species from overtaking the habitat and at the same time stimulates fire-adapted species to grow.

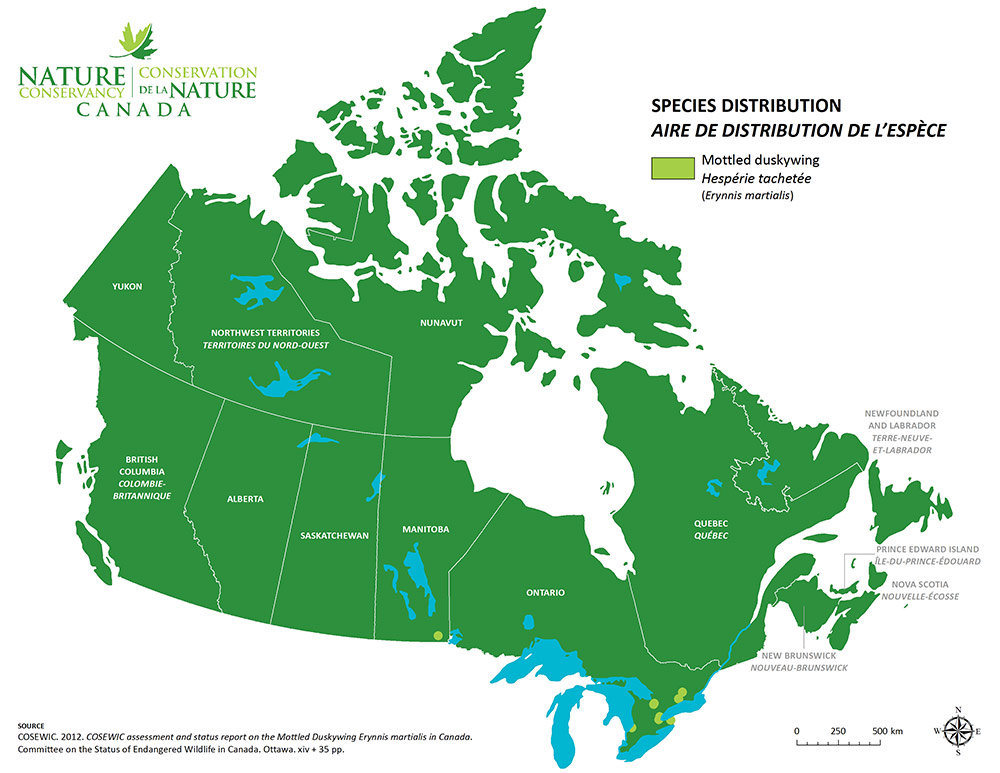

Where New Jersey Tea and Prairie Redroot thrive, there is another beneficiary: the Mottled Duskywing Butterfly (Erynnis martialis). A small and unassuming moth-like butterfly in the Skipper family, the Mottled Duskywing is a federally and provincially (in Ontario) endangered species. Like the Karner Blue butterfly, this species is non-migratory. Adults lay eggs on New Jersey Tea or Prairie Redroot, which are the only known food source species for the larvae.

Map from NCC, Source COSEWIC, 2012

Threats to the Mottled Duskywing and its host plants often go hand in hand: fire suppression resulting in habitat succession (although the relationship of this butterfly to fire is not fully understood), habitat loss or replacement, invasive species (in particular Dog-Strangling Vine) and deer over-browsing all play a role in the species’ decline. While New Jersey Tea and Prairie Redroot are not considered species-at-risk, the loss of large patches of these plants, their associated ecosystems, and other landscape features preferred by the Mottled Duskywing (such as puddles and hills) mean that quality Mottled Duskywing habitat is scarce. Remaining butterflies are thought to exist in small, isolated populations which leaves them more susceptible to disturbances.

invasive species (in particular Dog-Strangling Vine) and deer over-browsing all play a role in the species’ decline. While New Jersey Tea and Prairie Redroot are not considered species-at-risk, the loss of large patches of these plants, their associated ecosystems, and other landscape features preferred by the Mottled Duskywing (such as puddles and hills) mean that quality Mottled Duskywing habitat is scarce. Remaining butterflies are thought to exist in small, isolated populations which leaves them more susceptible to disturbances.

Fire Effects on New Jersey Tea

Government of Ontario - Mottled Duskywing Recovery Strategy

Join our email list to receive occasional updates about Network of Nature and ensure you get the news that matters most, right in your inbox.